What on Earth?

Lucy R. Lippard

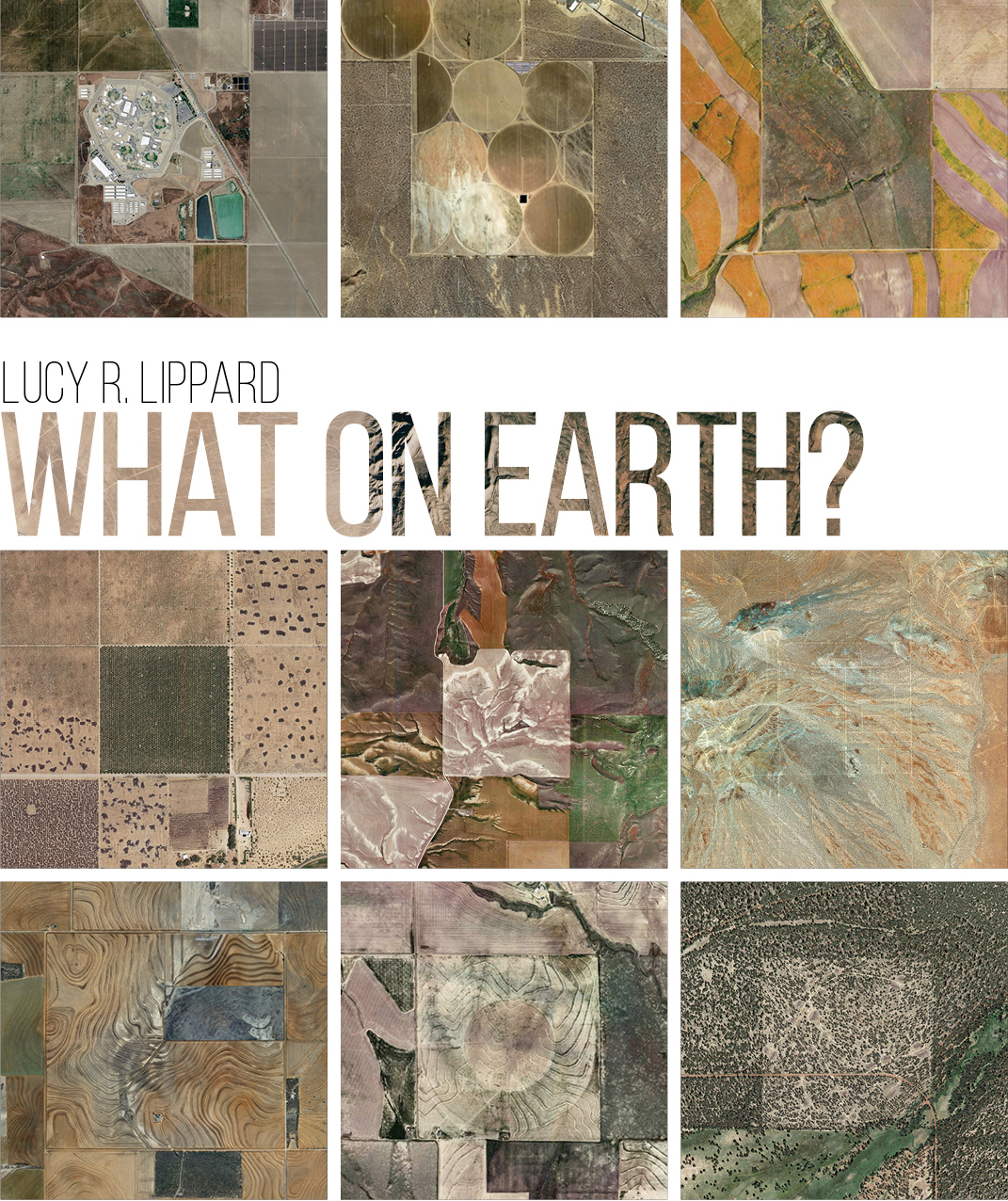

Images @the.jefferson.grid via Instagram, used with permission.

There is no better place from which to observe the geometry, geography, and geology of the planet than from a plane at several thousand feet. Glued to the window on a recent flight from New Mexico to Maine, I was struck by the designs below, inadvertently created by humanity through hard labor and greed, hope, and despair. It was a beautiful day, with cloud shadows racing across the land. The farther east we traveled the smaller were remnants of what we call wilderness – a bit depressing to a westerner accustomed to wider spaces. The sheer expanse of history and even geologic time is evoked as the land below us shifts and changes, as arid high desert and oil fields are replaced by wooded patches, as mountain ranges give way to plains, forests to farms, and streams to rivers (which sometimes resemble the historical roads they once were). Tiny dots dash along highways. Malls and subdivisions with an identical “variety” of architectural pastiche and curling culs-de-sac encroach on small farms. Scrawny third-growth forests await yet another clear cut. There are pits and there are erections, skyscrapers rising from the terrestrial origins of concrete. And finally there is the persistent sea, eating away at the Atlantic coastline. Personal landscape revelations, such as the incredibly labyrinthine coastline of Chesapeake Bay with its mansions, marinas, and industries suggest new narratives for the non-native that are hidden from limited views on the ground.

But where am I? Aside from the occasional comments of a chatty pilot, I have no idea. A pilot friend gave me a flight map, but it doesn’t help much. The gap between print and fast-flowing visual experience is too wide. I have long wished for a streaming audio that would provide a map in real time as we careen over the continent.

Our cultural landscape can be parsed as a chart of political and financial power. Vast oil fields evoke outrage at the federal government’s ongoing environmental deregulations. Miles of circle-irrigated agriculture in the desert raise questions of water supply and waste. But from this exalted viewpoint there is little hint of the climate chaos already evident to those whose heads are not in the sands of leisurely beaches and golf clubs.

This is not the iconic image of a “whole Earth,” the lovely mottled marble seen from space. Despite the height from which I peer down, it is a series of amazingly intimate views, dreamlike in their rapid disappearance, comparable to lived experience and fleeting memories. The abstract expressionist painter Joan Mitchell once said, “I carry my landscape around with me.” After spending a year in Devon, England, I found I could do the same, taking out-of-body hikes from Lower Manhattan across fields and hills and valleys that I once knew so well and were now so far away.

As a writer obsessed by place, flights are both fulfilling and frustrating. Haunted by the visible geometries and geographies and invisible geologies, I wonder if there is a way to fuse our patterned views from above and intimacy with known landscapes below. Would that help us non-professionals to understand more about landscape architecture at its roots, to learn the lessons of the bird’s-eye-view? Scale presents an interesting problem. Miniaturization is too easy an answer, but landscape architects are equipped to conceptualize the fusion of aerial and ground views, and perhaps they will be crucial participants in public education around issues of climate disruption.

Lucy R. Lippard is a writer, activist, sometimes curator, and author of 25 books on contemporary art activism, feminism, place, photography, archaeology, and land use including Undermining: A Wild Ride through Land Use, Politics and Art in the Changing West (2014) and Down Country: The Tano of the Galisteo Basin, 1250–1782 (2010). Co-founder of various activist artist groups, recipient of nine honorary degrees, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and other awards, she lives off the grid in rural New Mexico.