THIS MONTH’S CONVERSATION

In Conversation with Paul Paton + Anne-Marie Pisani

Sara Padgett-KjaersgaardFrom LA+ COMMUNITY

Image LA+.

Image LA+.To celebrate August 9, the International Day of the World’s Indigenous People, we look back at Sara Padgett Kjaersgaard’s interview with Paul Paton and Anne-Marie Pisani from LA+ COMMUNITY.

Paul Paton is a Gunnai, Monaro, and Gunditjmara man from South-Eastern Australia and the Chief Executive Officer at the Federation of Victorian Traditional Owner Corporations. He has had a long-standing career in not-for-profit organizations and government working together with Traditional Custodians to help facilitate Indigenous communities’ self-determination and connection to their lands. Anne-Marie Pisani is a landscape architect with experience in projects at multiple scales across the public and private sectors. She has been recognized by the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects for her contribution to the field by developing processes for engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Also partners in life, Paul and Anne-Marie are strong advocates for the inclusion of Aboriginal ways of knowing, being, and doing within the planning and design of urban and natural environments. Sara Padgett Kjaersgaard interviewed them for the LA+ COMMUNITY issue.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australia is diverse, both in language and landscape. Can you explain and situate this for people not familiar with Australia?

Paul: The Australian landscape holds the imprint of thousands of generations of Aboriginal people. Aboriginal people occupied the Australian continent for tens of thousands of years prior to European settlement living a lifestyle rich in culture, developed through a varied and complex set of languages, tribal alliances, trading routes, beliefs, and social customs that involved totemism, superstition, initiation, burial rites, and tribal moieties that regulated relationships and marriage.

These cultural practices involve a deep spiritual understanding of the environment and govern how Aboriginal communities live with and maintain the land, plants, and animals of their region. Stories are linked with culture as a way of passing information to younger generations. The stories often talk about creation and explain how natural elements were formed or how species came to be. Included in these stories can be knowledge of hunting locations, animal behaviors, and any restrictions or laws that apply to a species or region. Understanding the land through seasonal observations was once essential to survival and is today, essential to management. The arrival of Europeans irrevocably changed the lives of Aboriginal groups – effects that are still being felt today.

The recent Yarra River Protection (Wilip-gin Birrarung murron) Act 2017 recognizes the intrinsic connection of the Wurundjeri peoples to Melbourne’s Yarra River and its Country. How does this legislation highlight Indigenous understanding of land and what is its significance in broader discussions about sustainability?

Paul: First, I should mention that for Australian Aboriginal people the term “Country” incorporates the physical, cultural, and spiritual landscape as one. It includes what’s under the ground, on the ground, above the ground, in the sky, and the cosmos. The Birrarung (Yarra River) is connected to Wurundjeri culture spiritually through their creation stories, particularly the river as a life source that was etched into the landscape by their ancestral creator spirit Bunjil, the wedge-tailed eagle. The Birrarung—which in Wurundjeri language means “shadows of the mists”—flows approximately 240 km from the Yarra Valley into Port Phillip Bay passing through many wetlands, which were great sources of food and water, where Melbourne and its immediate suburbs now stand. Wurundjeri people once moved freely around the area based on the seasons and the availability of food. In winter, the Wurundjeri-willam clan regularly camped in the higher areas as the land near the river flooded. In spring and summer, they travelled more frequently, hunting and gathering food and visiting sacred sites.

Their spiritual connection to the many special places in the area extends back thousands of years through periods of extraordinary environmental upheaval that saw dramatic changes in the river. These stories of environmental change have been passed on through generations that enabled a highly attuned understanding of how to live sustainably and ensure that the land remains healthy. The Yarra River Protection (Wilip-gin Birrarung murron) Act is a positive step forward in recognizing the river as an entity unto itself and water as the provider of life to the land and its people. It also ensures that the rich knowledge that has been accumulated and passed on over those thousands of generations isn’t lost and is able to inform how we manage waterways now and into the future.

Australia has a number of different legal processes enabling Aboriginal people to claim traditional ownership of their ancestral lands and to protect their cultural heritage. Is there a difference between the work you do with communities who have a formal determination of traditional ownership in comparison to those that haven’t?

Anne-Marie: I believe it is important to be as inclusive as possible when working with Aboriginal communities. In the [southern Australian] state of Victoria, there are currently 11 Traditional Owner groups (or “Registered Aboriginal Parties”) recognized by the Aboriginal Heritage Act, which have responsibility for managing and protecting Aboriginal cultural heritage in their ancestral Country. There are also a number of Aboriginal Corporations across the state that undertake a vital representative role for their communities, but which are not formally recognized under the Aboriginal Heritage Act.

Clients sometimes provide direction to only engage with the parties recognized under the Aboriginal Heritage Act. This can be a difficult situation: although Registered Aboriginal Parties have gone to great lengths to confirm their ongoing connections to their Country through court proceedings, this doesn’t mean that other Aboriginal groups have any less connection to Country. Being inclusive through engaging with all of these groups shows the community that we understand that the official recognition of groups is a colonial construct and that we recognize and acknowledge the deep connection that all Aboriginal people have with Country.

Paul: Traditional Owners have inherent cultural rights to maintain their cultural practices alongside specific cultural obligations to care for Country. It is the obligation of the states under the United Nations Declaration of Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) to support these. Formal recognition gives states confidence that they are dealing with the appropriate people who hold those connections, but it can also leave gaps in consultation processes where groups haven’t achieved this status. States need to increase their capabilities in order to engage with all communities. From an Aboriginal community perspective, our personal relationships and connections have stood the test of time through thousands of generations to the point of us knowing who is connected to where and how. It is, however, important that consultation isn’t confused with recognition and there would be possible implications if the two aren’t clearly defined throughout the process. The bottom line is that there must be equity and opportunity provided to all irrespective of status, and the only way to achieve this is through increasing one’s own capability to know who the communities are and establishing relationships with them.

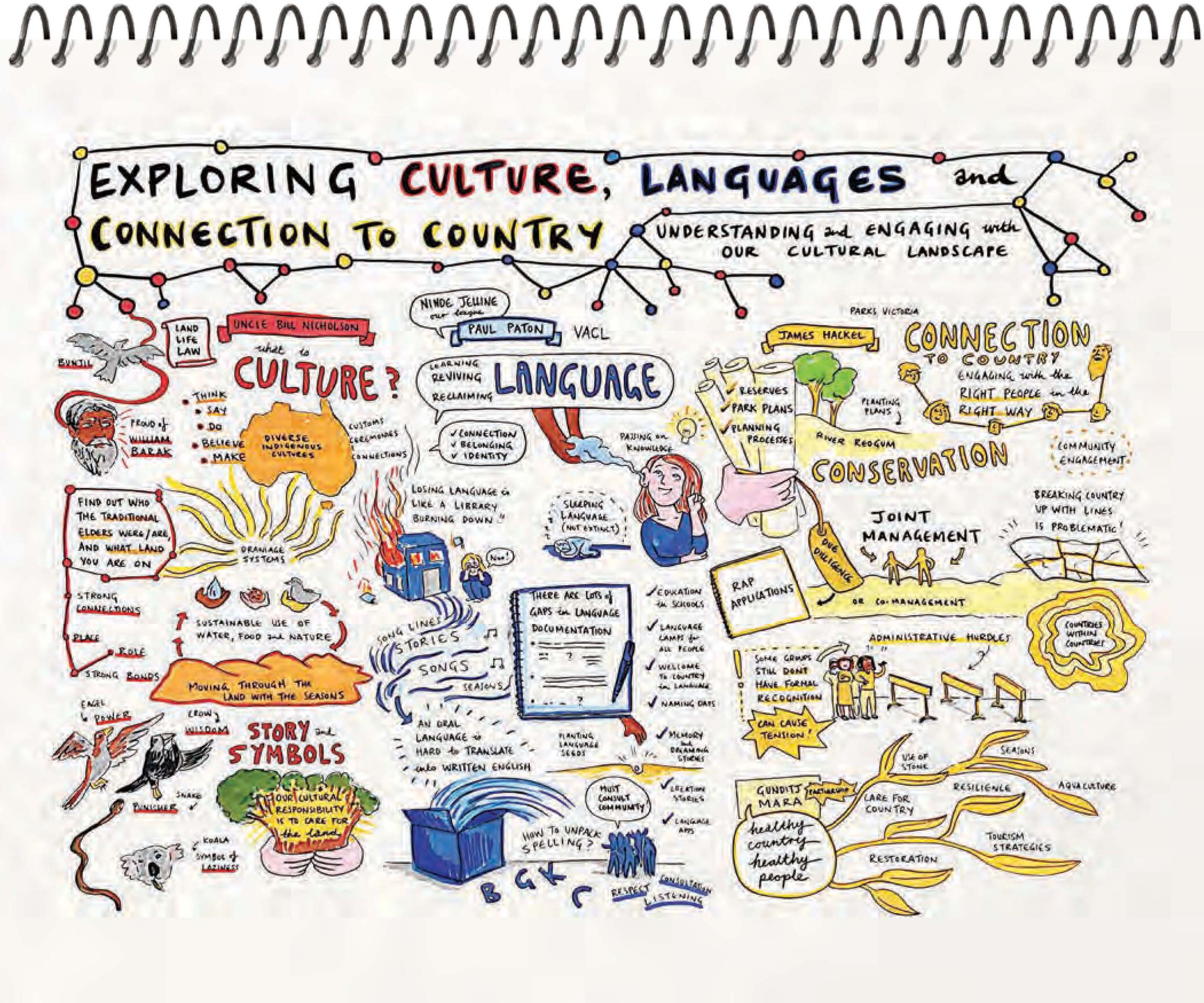

Image by Sarah Firth

The Australian state of Victoria has a high number of joint management plans with Traditional Owners. What are the cultural and ecological benefits of this type of land management?

Paul: Joint management is a formal partnership arrangement between Traditional Owners and the state where both share their knowledge to manage specific national parks and other protected areas. Government agencies with land management responsibilities for Victoria’s state and national parks work together with Registered Aboriginal Parties to enable the knowledge and culture of the Traditional Owners to be recognized through participation in the decision-making and management of public land.

The cultural benefits of these arrangements are such that, similar to the Yarra Protection Act, traditional knowledge which has been accumulated and passed on through generations is able to be incorporated into the ongoing management of land. This, in turn, recognizes and restores the stewardship that Aboriginal people hold toward “caring for Country” – a traditional role that is integral to both community and individual health.

The Australian landscape is unique, with ecosystems that have been influenced and sustainably managed by Aboriginal people for tens of thousands of years. The arrival of Europeans has had a dramatic effect on the landscape, largely due to introduced land management practices that weren’t appropriate to this place. Large-scale clearing of land for farming, European agricultural practices, and water diversion from the landscape are just a few examples of significant change that have had detrimental effects on the land. Another is the failure to recognize the importance of traditional practices of controlled burning used by Aboriginal people to reduce the risk of unmanageable bushfires and to regenerate flora. Joint management is a mechanism to reintroduce traditional knowledge and practice and hopefully reverse some of these effects. The enormous destruction of the 2019 bushfires throughout Australia is a clear example of this impact on the landscape to both flora and fauna.

Can you tell us about any specific methodologies you employ that enable you to undertake work with Aboriginal communities more successfully?

Anne-Marie: When I am engaging with Aboriginal communities I aim to undertake a respectful approach through my actions, as well as through consultation. These actions extend well beyond verbally acknowledging and paying respect to the Traditional Owners and Elders of the Country that I am working on. It means ensuring early engagement, so as to allow time to build a trusting relationship and ensure cultural protocols and decision-making processes of the community can be incorporated into the project timeframe; or alternatively, and better still, to allow it to drive the project timeframe. Often project timeframes are tight, but the earlier the conversation begins to start building this relationship, the greater and more positive the influence will be on the project. Strong everyday relationships are built on informal conversations – this approach is no different. Consider these informal discussions every time, prior to getting down to business. I don’t believe there would be many people who would disclose information they held to someone they didn’t know and were unsure if they could trust?

Traditional Owner Elders are sought after to provide advice on an enormous range of issues affecting their communities and as there are only a small number of them in any community, we cannot expect them to have an in-depth understanding of what the design profession can offer. We cannot assume the community understands design or technical language, so it’s important to use plain English in conversations. At the same time, we need to really listen to what is being spoken – this is often referred to as deep listening. This is not as easy as it sounds. Everyone can hear what someone says, but it takes a different skill—often learnt over many years—to really listen and hear the message behind the spoken words.

Lastly, if the Traditional Owners are bringing their knowledge (being their commodity) to the table, we must ask ourselves, what are we bringing – both personally and professionally? It needs to be more than just the project delivery. Projects are often opportunities for possible employment for communities, but they are just that—opportunities—and they generally only come to fruition in the long term. We need to consider other community benefits as part of the process.

Working with Aboriginal communities requires deep listening and continuous reflection. When have you got it wrong and what lessons did this teach you?

Anne-Marie: I have been fortunate enough to live in various locations across Australia, from Far North Queensland to southern Australia and across to the southeast, working with a number of Aboriginal communities. Experiencing the diversity of cultures in these communities made me appreciate that I needed to continue to build on my understandings of what I had learnt from a previous community, not rely on it as a general understanding for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures.

When I first started engaging with Aboriginal communities I did extensive reading about Aboriginal culture and didn’t properly appreciate that the information was often written from a non-Aboriginal perspective. I was quickly reminded that Indigenous knowledge was passed down orally and that written accounts don’t always capture the true cultural meaning. As I built on my experiences engaging with communities, I continued to gain a deeper understanding of an Aboriginal way of seeing. Speaking, or “yarning” with a community would always leave me much richer for the experience!

What recommendations do you have for landscape architects and designers who are at the beginning of building connections with First Peoples?

Anne-Marie: Considering our profession with our direct relationship with the landscape through developing, manipulating, and rehabilitating I continue to find it quite astonishing the number of people that have never met or spoken to an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person. Granted, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people make up only a very small minority at just over 3% of Australia’s population, but how can we not seek Indigenous knowledge and understanding of Country to ensure the long-term sustainability of this landscape?

I speak to many people who are concerned that they will say something inappropriate or be misunderstood about their intentions when speaking with Traditional Owners. If you ensure you consider a respectful approach of engaging, then this reduces the chances of misunderstandings. Communities are very attuned to genuine, respectful engagement. Bringing an open mind with a non-presumptive attitude to the conversation will stand you in good stead.

Paul: The first step in building connections with First Peoples is to ensure you correctly seek out who it is you should be speaking to. If you are interested in engaging the community in a general nature, then reaching out to an Aboriginal organization is a great first step – they will be able to advise on the right people to speak to initially. But if you are interested in building a relationship with a particular community to discuss more site-specific issues, then you really need to speak to the Traditional Owners for the area. Developing a relationship with the Traditional Owners is the first step, but even more important is to continue to build on the relationship – to continue the conversations. True engagement requires a long-term relationship based on trust, respect, and honesty.