In Place Over Time: A Case for Longitudinal Action Research

Anne Whiston Spirn

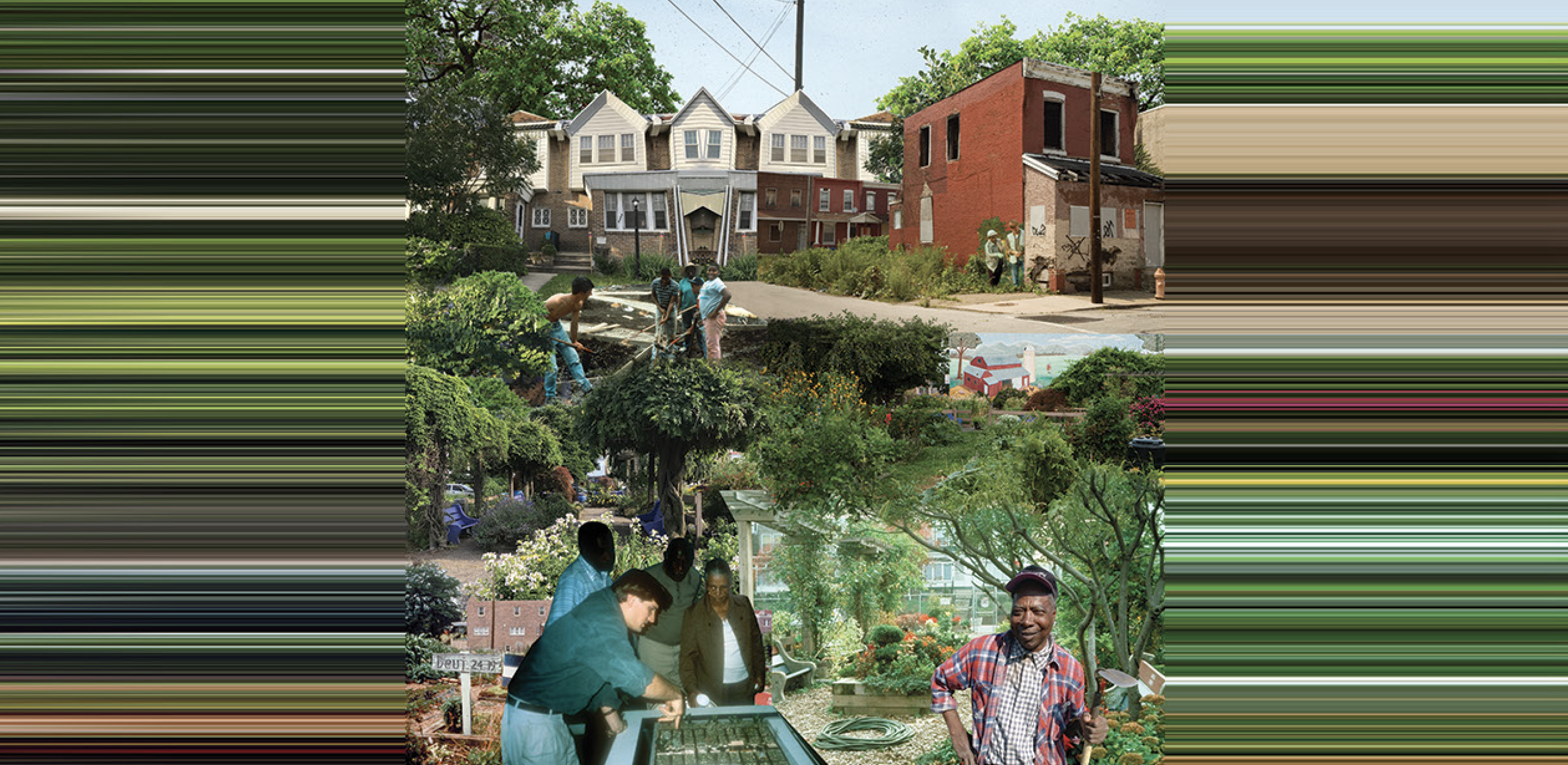

Collage by Melissa Isador, courtesy of Anne Whiston Spirn and WPLP.

In 1987 I would not have predicted that, more than three decades later, I would still be engaged with West Philadelphia’s Mill Creek watershed and community. Initially, I did not intend to have a long-term relationship with this place. It started as a four-year, action research and community service project, with the expectation that I would turn over my findings and recommendations to the Philadelphia City Planning Commission, and that the “official” planners would take them on board in their 1994 Plan for West Philadelphia. But, they didn’t. Outraged and perplexed, I determined to persist, which led, over the years, to deeper and deeper relationships with the place and its people. What began as research driven by my own goals, grew into a program of mutual teaching and learning with children and adults in the Mill Creek community.

In 1986 I moved to Philadelphia from Boston, where I had been studying urban vacant land as an opportunity both to restore the urban natural environment and to rebuild inner-city communities. There, I discovered a correlation between the buried floodplain of former streams and large tracts of vacant land and envisioned a potential solution to Boston’s most pressing environmental problem, the pollution of Boston Harbor by combined sewer overflows (CSOs). Boston, like Philadelphia and many older cities, has combined sanitary and storm sewers, so, after a rainstorm, torrents of sewage rushed into rivers and harbor. Billions of dollars would be spent to build an enormous plant to treat combined sewage from the Boston metropolitan region. I proposed an alternative: prevent stormwater from entering the sewer system in the first place by employing “green” infrastructure to detain or retain runoff. Vacant land in the valley bottoms of inner-city communities could be transformed into parks, their construction and maintenance paid for by funds for water infrastructure. I cited as precedents Frederick Law Olmsted’s designs for Boston’s Fens and Riverway in the late 19th century. My proposal received a lot of attention, but Boston decided to build a new sewage treatment plant instead. When I moved to Philadelphia I knew that, at some point, the federal Clean Water Act would force Philadelphia to deal with pollution from CSOs, and I hoped to persuade the city to adopt the approach I had advocated for in Boston.

At the University of Pennsylvania, I joined with colleagues at Penn and Philadelphia Green in a proposal to the Pew Charitable Trust for funding to “green” West Philadelphia through the design and construction of community gardens. With an eye to extending the Boston research, I persuaded the others to enlarge the project’s scope from community gardens to the restoration of the natural environment at large. I was particularly interested in the Mill Creek watershed, which comprised about half of our study area. Mill Creek is a watershed that was drastically reshaped as it was densely urbanized, a river buried in a sewer, and a neighborhood with severe poverty. The correlation between vacant land and the buried stream was clear in the Mill Creek neighborhood. How do you restore the urban natural environment in such places at the same time as rebuilding those neighborhoods, and do so in synergistic ways? My work in Mill Creek would explore how this might be accomplished.

Our work during the first summer of 1987 went against the norms of “proper” research practice, an orderly progression from data collection and analysis, to a synthetic plan for the future and identification of the character and location of design experiments, to detailed design. Instead we were immediately thrown into designing and building community gardens. The process felt upside down, the designs uninformed by research. The design “cases” were not chosen as representative of particular conditions, nor were their locations deliberately selected as strategic; they were vacant lots where neighbors wanted a garden. After a few months, however, I realized what rich insights this mixed-up process had yielded. Building a project was not the end point. It was a beginning that revealed misleading or overlooked data. The process of bringing a project to fruition and reflecting on the result also generated ideas for an approach to planning as a framework for action, where all citizens, groups, and agencies have a role to play. From then on data collection and analysis, planning, design, and construction, all proceeded apace, each activity informing the others.

The community garden, as it turned out, was a microcosm of community that offered lessons for designing the neighborhood and city. “This garden is a town,” Hayward Ford, president of Aspen Farms Community Garden in Mill Creek, told us, “we have everything but a penal colony.” The garden’s plots were laid out in a grid, each individual territory bordered by paths, like streets. There was a common infrastructure: a drip irrigation system and a compost pile. But, “It isn’t all 50 beds of roses,” Ford said. There are 50 different people with 50 different ways of seeing things and 50 different ways of doing things. And everybody, of course, is always right.” To adjudicate these differences, the gardeners elected leaders and voted on contentious issues. Like pioneers, community gardeners who settle a vacant lot must decide how to govern themselves and how to lay out the garden, and its form reflects its political structure. The grid of plots at Aspen Farms, for example, reflected its democratic organization. We also found an “anarchist” garden, whose haphazard layout reflected the fact that there were no rules, and a “benevolent dictator” garden that appeared to be the garden of a single individual, with no clear boundaries between plots. It was governed by a dictator who made the rules, chose the members, laid out their plots, and selected the plants.

By 1988, Aspen Farms was a well-established garden, but it lacked a meeting place to accommodate pot-luck suppers and visiting school groups. Students in my landscape architecture studio were asked to design a new meeting place. The students—who were white or Asian and mostly middle class— began by getting to know their clients and the neighborhood; each student stayed for a weekend with one of the gardeners. I wanted my students to understand the difference between quality of life and standard of living. You can have a high standard of living and a low quality of life. You can find people in tough situations in low-income neighborhoods who have a high quality of life, and you have to recognize and respect that. They create it for themselves with their family, with their church, or with other groups.

All the students proposed a circular or square place for meeting, a cliché. One student, John Widrick, decided to revisit Aspen Farms and ask for comments on his design for a circular meeting place in a central location. He was unprepared for the reaction of polite horror. What we had idealized as one big community was actually several smaller groups, each with its own territory and leaders. John’s original scheme not only displaced several garden plots, it disposed of most of one group’s territory. He began again. His new design created a meeting place by widening the central path, so the space given up to create the common area would be evenly shared. When the students presented their designs to the gardeners, they chose to build John’s. The path became the garden’s “main street,” lined with benches and raised flower beds, which formed boundaries between the public space and adjacent garden plots. Small openings between planters were gateways leading to the garden plots beyond. Groups of plots formed small neighborhoods within the larger garden, which competed with each other for the best flower beds along the main path outside the gate to their plots. The design for Aspen Farms’ main street turned conflict and competition into common benefit and has served the garden ever since.

On the ground, working with community gardeners, I learned how diverse the Mill Creek neighborhood was in terms of residents’ income, employment, family history, family composition, and educational attainment. Aspen Farms took up a half block on the corner of 49th and Aspen streets. Wellkept rowhomes framed the garden on two sides; public housing faced it across 49th Street. One block down the street to the north was a vacant block. One block to the west, a third of the houses were vacant. This pattern repeated throughout the neighborhood: blocks of well-kept homes adjacent to blocks of vacant land and vacant houses.

Our maps of the neighborhood’s demographics, based on 1980 US Census tracts, did not reflect what I observed on the ground. Each census tract encompassed more than thirty blocks, whose size obscured the block-to-block diversity. Data for the census tract to which Aspen Farms belonged, for example, indicated that the population included 4,227 black residents, 166 whites, 10 American Indians, and seven Filipinos. The median household income was $9,550 and the per capita income, $3,846, with 45% of the population near or below the poverty level. Nine percent of the housing units were vacant. Given the stark variation from block to block, many residents actually were much better off (with higher incomes, living on blocks with no vacancies) than the tract statistics would have predicted, and many were much worse off than the numbers indicated. Certain census data was available at the scale of the block, which clarified some factors, like the fact that although there were 166 white residents, 120 of them lived in a mental hospital. But even at the block scale the census statistics were misleading. The US Census defined a block as being bounded by streets, as opposed to a social block, with houses facing each other across a shared street. At times, the census block combined social blocks that were worlds apart. And the census had nothing to say about residents’ educational attainment; years later, I learned that people with graduate degrees may live in the same block as others who have no high school diploma, all part of the block community. Relying on statistics without field experience can take you down the wrong road. You may think you understand because you’ve got statistical data and you can do all sorts of calculations. But the numbers may bear little relation to reality.

The community gardeners had an intuitive understanding of natural processes in cities. Aspen Farms sloped down toward the valley bottom where Mill Creek once flowed, where it had been buried in a vast sewer. Hayward Ford knew that the soil was wetter on the garden’s low end; the plots there didn’t require as much irrigation as those upslope. We discussed the continuing subsidence along the buried flood plain of Mill Creek and the idea of detaining or retaining rainwater to reduce combined sewer overflows. This made sense to him, but, evidently, not to the city’s planners.

After the City’s 1994 Plan for West Philadelphia ignored the hazards posed by Mill Creek’s buried flood plain and discounted my proposals, I decided to focus on the Mill Creek community, to inform residents about the buried floodplain, and to work together on proposals. I knew many community gardeners, but they were mostly seniors. To reach the broader adult community, I decided to work with their children. The University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Community Partnerships encouraged faculty to work in West Philadelphia public schools. I met with the director, Ira Harkavy, and volunteered to work with a school, preferably a middle school, but definitely one on or near the buried floodplain. Several schools qualified, but Sulzberger Middle School was one block from Aspen Farms, and Mill Creek once flowed right through the school site. Unfortunately, the principal was resistant to having a Penn professor and students come into her school. It wasn’t until she learned about my work with Aspen Farms that she agreed to meet. Hayward Ford came with me, and so began our partnership with the garden and the school.

What began as a community-based, environmental education program organized around the urban watershed grew into a program on landscape literacy and community development, where children learned to create websites as a storytelling medium. From 1996–2001, hundreds of children at Sulzberger and students at the University of Pennsylvania learned to read the neighborhood’s landscape; they traced its past, deciphered its stories, and told their own stories about its future, some of which were built. The tools they used were their own eyes and imaginations, the place itself, and historical documents such as maps, photographs, newspaper articles, census tables, and redevelopment plans. The program had four parts: reading landscape, proposing landscape change, building landscape improvements, and documenting proposals and accomplishments. The first two parts were incorporated into both university and middle-school curricula during the academic year; all four were integrated in a four-week summer program. The summer program for Sulzberger students was organized and led by my research assistants. In the mornings the group met either at Aspen Farms, where they built a pond and compost bin, or at Sulzberger, where they constructed a topographic model of the Mill Creek watershed and learned how to program a website. Their website, “SMS News,” was posted on the West Philadelphia Landscape Project website.

Our Mill Creek Project at Sulzberger got a lot of attention. People from foundations, from all over the country, observed the classroom. Pennsylvania’s governor invited the middle school students to present their website as part of his 1998 Budget Speech to the State Legislature, which gave them a long, standing ovation. In 1999 Sulzberger was the subject of a report on NBC Evening News. In 2000, President Bill Clinton visited the school.

Once I started working in the school I had a different relationship to adults. For example, when Hayward Ford would introduce me to someone in the neighborhood, “This is Anne Spirn, she’s working with children at Sulzberger Middle School,” that person would say, “Thank you. Thank you.” And then they would refer to “our children,” even if they didn’t have any children. Where I grew up, in a predominantly white, middle-class suburb, someone would talk about “my children” or “our kids,” meaning those two kids. To speak of “our children,” meaning all the children of the community, was something I had never heard before. I later learned that this is common in African American communities. To take collective responsibility for all the children of a community is a tremendous asset.

The Mill Creek Coalition, a group of community leaders dedicated to improving the neighborhood, heard about my work with the school and asked me to make a presentation about the buried flood plain, where it was and what to do about it. Frances Walker, chair of the coalition’s environment committee asked me to join, and, in 1999, we decided to do a pilot study to assess damage in houses on Mill Creek’s buried floodplain. I proposed an area for our research and Crystal Cornitcher, president of the Mill Creek Coalition, said, “We have to include my block.” “But it’s not on the buried flood plain” I replied. “Yes, it is,” she said, “We have terrible water problems.” Crystal’s block was well above the valley bottom, but the water damage was severe. Some houses had slanting floors and rotted out floorboards, some had mold on basement walls and mortar coming out of the joints between bricks in the foundation. Outside, yards sloped toward the houses, and downspouts were disconnected so that rainwater flowed into the foundations. Our pilot study led to the realization that the water issue was much bigger than the buried floodplain, and that it likely affected a large segment of the population. This opened up an opportunity both to deal with water problems and build a local economy. Repairing roof and downspouts could be the foundation for small businesses. We would not have come to this idea without Crystal Cornitcher insisting that there was a water problem on her block. As an outsider, I would not have been able to get into people’s homes and down into their basements. There were many cases like this where I would not have made important discoveries had I not been working with people in the community. We were engaged in a process of mutual teaching and learning. As I learned, my capacity for working with the community increased, as did my capacity as a researcher and as a planner and designer.

I had been meeting with engineers from the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD) since 1996, when staff of the US Environmental Protection Agency’s regional water division, increasingly concerned about Philadelphia’s combined sewer overflows (CSOs), had brought us together to discuss the potential of stormwater detention and green infrastructure to reduce CSOs. In 1999, Howard Neukrug, director of the PWD’s newly formed Office of Watersheds asked me to take a group of engineers on a field trip to Mill Creek to show them sites appropriate for stormwater detention. An immediate outcome of our field trip was the PWD’s decision to design and build demonstration projects that would detain stormwater and function as an outdoor classroom for Sulzberger Middle School. The PWD got a grant to fund the project and pledged to work with teachers and students at Sulzberger. They hired one of my research assistants to work on the project and, in 2001, cosponsored the summer program on the urban watershed with Sulzberger and met with members of the Mill Creek Coalition.

About that time I asked an old anthropologist, “How do you know when a project is over?” “It will come to a natural end,” he said. In 2000, I had moved to Boston and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, but continued to work with teachers at Sulzberger until 2002, when the state took over the Philadelphia School District. The state turned over the management of Sulzberger to Edison, Inc. Edison dismantled the Mill Creek Project, and key teachers left in protest. In 2009, Hayward Ford died. Two years later, Crystal Cornitcher died, and I began to understand what that anthropologist had told me. But then Fatima Williams contacted me. The last time I’d seen her, she had just graduated from Sulzberger. In 2012, I met with Fatima for the first time since 1998. She was 28 and married with three kids. She told me how learning HTML as an eighth-grader, as part of our Mill Creek Project, had led her from homelessness to a career in Web development, and I realized that I’d started out on a whole new phase of the West Philadelphia Landscape Project. I reached out to others who had been part of WPLP at some point during three decades: teachers and children (now adults, like Fatima) from Sulzberger, community leaders, professional colleagues, former research assistants. What they told me was revelatory. The teachers described how the project had transformed their careers and the entire school. Howard Neukrug, newly appointed as Philadelphia Water Commissioner, recalled how our field trip to Mill Creek led to Philadelphia’s acclaimed plan: Green City, Clean Waters.

With the US Environmental Protection Agency threatening to levy huge fines on the city for polluting water, Neukrug had persuaded the PWD to reduce combined sewer overflows through green infrastructure. Their plan, Green City, Clean Waters—now recognized as a landmark of policy, planning, and engineering—calls for reducing impervious surfaces in the city by 30% by 2020 in order to capture the first inch of rain to fall in a storm. If the plan works, it will save the city billions of dollars and provide the benefits of jobs, educational opportunities, and neighborhood development. But will it work (physically), and can it be done (economically, politically)?

To help test and refine Philadelphia’s plan, in 2010 and 2011, my MIT students studied the ultra-urban Mill Creek Watershed. During their fieldwork, they encountered many questions from residents who were curious about what they were doing. When the students described the Green City, Clean Waters program, people were skeptical. “No jobs, no hope,” one man told them. His response inspired them to propose a program that connects low-income communities with “green-collar” jobs through education, job-training, and the construction of local prototypes. My Ecological Urbanism class at MIT continues to study the Mill Creek watershed and to make proposals that integrate environmental restoration, community development, and the empowerment of youth, taking a top-down/bottom-up approach that brings together public officials and neighborhood residents. In 2015 I co-taught the class with Mami Hara, then chief of staff at the PWD. Our students devised Philadelphia Green Schools, integrating three movements—green schoolyards, community schools, and place-based education— where schools are at the heart of community development.

In 2018, my work in West Philadelphia took a new turn. Frances Walker called for help. After her mother died, her dream was to move back to the family home, but she was in poor health, on a tiny fixed income, and the house was uninhabitable. Rain poured in through a hole in the roof, mold had taken hold, and Frances didn’t have the $15,000 for repairs. Philadelphia has a program to help low-income homeowners maintain their homes, but Frances didn’t qualify because she did not have clear title to the house. Nor did anyone else. Her mother died without a will. There were 17 heirs, including Frances. The home was an “heir house” with a “tangled” deed. Frances knew what happens to such houses. Without a title, family members cannot sell the house, and clearing the title is a prolonged and costly process. The heirs can’t agree what to do, and the houses sit and deteriorate. Then they are torn down.

In neighborhoods across Philadelphia (and the US), thousands of houses stand vacant because no one has clear title to the property. The abandonment of a single rowhouse exposes adjacent properties to risk from rot, mold, vermin, fire, and the potential for illegal activities carried on by squatters in the abandoned property. Waiting to address these problems after houses are abandoned and after they deteriorate and collapse is expensive. Widespread abandonment depletes the city’s housing stock and creates another problem: extensive, scattered vacant land.

Meanwhile, after more than a half century of redlining and disinvestment, outside capital is flowing into West Philadelphia’s low-income, African-American neighborhoods, and homeowners are losing their homes through predatory lending (reverse-redlining) and the unscrupulous practices of aggressive speculators. To make matters worse, tangled deeds make it difficult for heirs to claim a deceased relative’s property. These neighborhoods are in dire need of investment, but not through tricking and cheating residents out of their homes. My students and I are working with Monumental Baptist Church and its community development corporation, to develop an action plan to address this crisis and to study how flows of capital, like flows of water, shape the landscape of West Philadelphia.

There are tremendous advantages to staying engaged in a single place over many years. You build trust with people, you build relationships, not just with people who live in the place, but also with those who are working for public agencies or in the community as teachers. Over time, you accumulate knowledge, build networks, and gain understanding that those who work in a place for only a few years can never know. When you are in a place over time, making a series of proposals, staying engaged, watching what happens, evaluating the results, was it a success, was it a failure, adapting, you learn a tremendous amount.

To test my ideas, I put them on the line in the form of actions. When there’s a failure, it reveals a flaw in the theory: it didn’t encompass enough or it didn’t take certain things into account, things that had been invisible to me until the failure revealed them. I may start out with one idea, and then, the process of action and reflection modifies that idea or generates a new one. Some of the most important ideas that I developed over the course of these last 30 years emerged from the work, they were not ideas that I already had when I started. For example, in Boston, when I found a correlation between large swaths of vacant land and the buried floodplains of former streams, that discovery emerged from looking for ways to restore the urban natural environment and trying to explain the patterns of vacant land I found in low-income neighborhoods. At first, I didn’t regard water as key, that realization emerged from the research, when I made the connection between vacant valley bottoms, buried sewers, and polluted harbor. Then the failure to convince city planners and engineers to consider my proposals revealed barriers to innovation in urban design and planning that would need to be overcome. In action research, one thing leads to another.

My research has been enhanced and enlarged and in some cases transformed by my relationships and experiences in this community. When I started out I didn’t think of youth as probably the most important agents for change in a neighborhood like Mill Creek; I went into the middle school in order to reach the adults. What I discovered once I started working in the middle school was how fresh and open, imaginative, intelligent, and ready to act these young people were. So I expanded my research questions. How can urban design and planning restore the urban natural environment, rebuild neighborhoods, and empower youth, simultaneously and synergistically? How can this be accomplished in ways that are just, so that people who live in a place are not displaced? How can designers and planners weave together threads of environment, poverty, race, social equity, and educational reform, along with aesthetics and function? For the past 35 years I have sought to demonstrate how this might be accomplished and to develop theory and methods to support this kind of practice. The partnership with people of the Mill Creek community, engaging with them in a mutual process of teaching and learning, has been fundamental and indispensable, a source of insight, inspiration, and friendship.

Anne Whiston Spirn is the Cecil and Ida Green Distinguished Professor of Landscape Architecture and Planning at MIT. Her books include The Granite Garden (1984), The Language of Landscape (1998), Daring to Look (2008), and The Eye is a Door (2014). This essay is an excerpt from her forthcoming book The Buried River. Spirn received Japan’s 2001 International Cosmos Prize for “contributions to the harmonious coexistence of nature and mankind” and the 2018 National Design Award for “Design Mind.”